Nikolai Sadik-Ogli

Harry Smith (1923 — 1991) was an American anthropologist, collector, occultist, record producer, painter, polymath, and alchemist. He is now finally becoming publicly remembered, revered, and celebrated after having lived a life of extreme and deadly serious excess and artistic idealism exclusively in the underground and on the margins of society.

As Harry Everett Smith was born 100-years ago on 29 May 1923 in Portland, Oregon, the increasing appreciation of his important work has been celebrated this centenary year primarily through the release of two major, long-overdue productions – the first full-length biography, Cosmic Scholar, along with the first fully dedicated retrospective art exhibition, “Fragments of a Faith Forgotten.”

Released in August of this year, Cosmic Scholar by eminent jazz historian and biographer John Szwed represents the first complete biography of Harry Smith’s long and varied existence. It deftly follows the trajectory of his strange and marginal life as much as possible given its chaotic, unstable, and unsustainable circumstances. While providing a wealth of new information, it also expertly discusses the circumstances surrounding the creation of Smith’s most important works, particularly in music and film, against the backdrop of the general cultural environment and trends of their respective times.

In summary, after graduating from high school, Smith briefly first attended the University of Washington and later the University of California at Berkeley for some semesters each before settling down to a completely independent existence in the latter area. While there, he took advantage of the World War II shellac drive war effort that allowed him to amass a collection of some twenty-thousand old records that provided the source material for his later and much celebrated three-volume Anthology of American Folk Music.

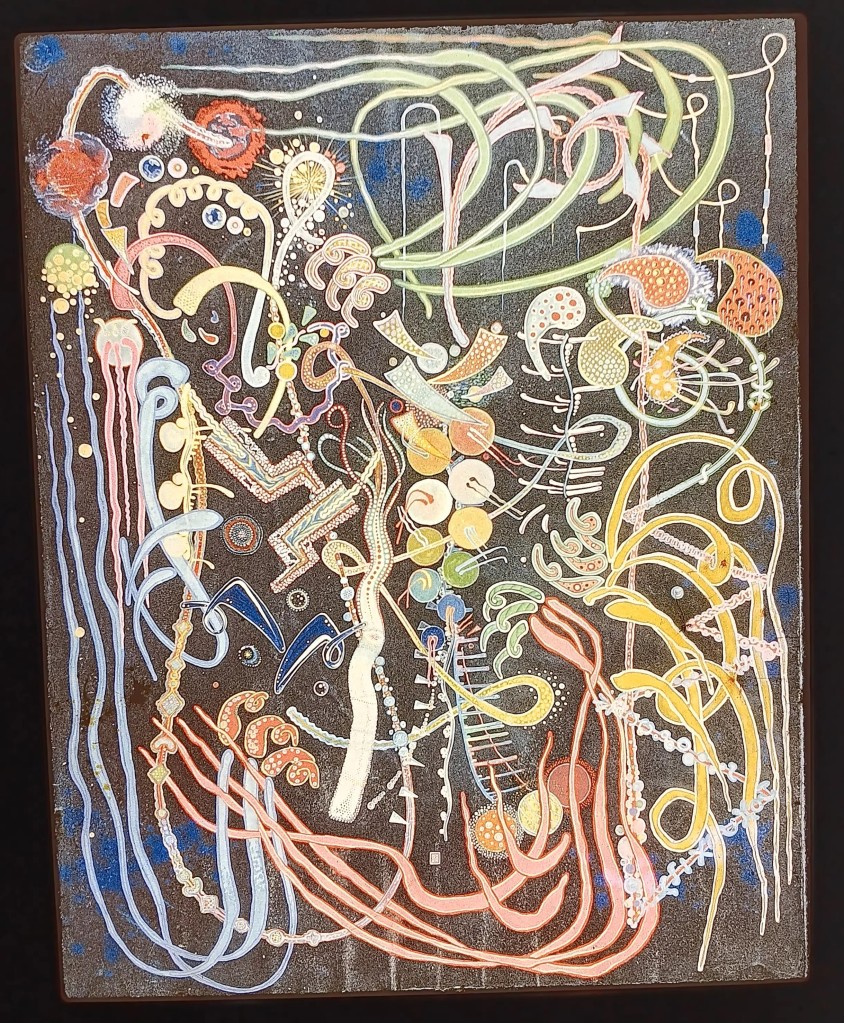

Smith next moved into the African American Fillmore district of San Francisco, where he painted the murals for the important jazz club Jimbo’s Bop City. Further in response to this most new and exciting music of the time, he started painting impressionistic transcriptions depicting the melodies, rhythms, and instrumental solos of certain jazz records in abstract graphical form. Privately in his apartment, Smith would play the records and use a pointer to demonstrate the different areas of the paintings that corresponded to the different parts of the music. Expanding on such ideas, he later painted similarly inspired animated abstractions directly onto film, thereby making movies without needing to have or use a camera. He showed these films at the San Francisco Museum of Art’s (today the SFMOMA) “Art in Cinema” screening series, occasionally accompanied by a live jazz band improvising along to them.

Smith moved to New York City in 1951 with the intention of meeting Marcel Duchamp and remained there for most of the rest of his life. He worked for Lionel Ziprin’s companies Inkweed Studios and Qor Corporation, conducted research for inventor and philosopher Arthur Young, and throughout his life continued collecting mountains of books, records, and a variety of different kinds of anthropological items, such as Tarot card decks, paper airplanes, and Ukrainian Easter eggs, all the while also continuing to produce art, films, and recordings. Amazingly, all of his activities were conducted while regularly living an unstable and usually heavily intoxicated life, scrounging or asking for money wherever he could, including from surprisingly wealthy patrons such as Peggy Guggenheim and established organizations such as the Anthology Film Archives (and its predecessor the Film-Makers’ Cooperative), all the while living in various hotels throughout the city in a manner that basically represented an existence similar to that of a typical bum. During the last few years of his life, to save him from complete squalor, Allen Ginsberg invited Harry to present lectures and otherwise exist as ‘shaman-in-residence’ at the Naropa Institute (now Naropa University) in Boulder, Colorado. Transcriptions of the lectures along with copies of the readings prepared by Smith have also been published this year by Raymond Foye as Cosmographies. During the last months of his life, the Grateful Dead’s Rex Foundation paid Harry’s rent at the Chelsea Hotel until his passing on 27 November 1991.

Ultimately, as indicated by this brief outline as well as the subtitle of the new biography – “Filmmaker, Folklorist, and Mythic” – numerous epithets and other descriptors have been applied by necessity to Harry Smith. As indicated, no single descriptor is able to sufficiently describe the full length and depth of his varied, multi-faceted work.

The Anthology of American Folk Music, “I saw America changed through music.”

The Anthology of American Folk Music was compiled by Harry and released in 1952 by Folkways Records, and it remains his best-known piece of work. It is a multi-album compilation of 84 tracks featuring a variety of American musical traditions recorded in the late 1920s, including country, blues, Cajun music, and cowboy songs. While most of its recordings originated in the American South, “Moonshiner’s Dance, Part 1” – selection number 41 situated near the center of the set – represents an anomaly in that it features the Frank Cloutier Orchestra, an early jazz kind of band, complete with horns and drums, from St. Paul, Minnesota, in the American Midwest. (Listen at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qA0vzO0FVXc)

Moreover, as a medley of other, older tunes from the even earlier Victorian era – “When You and I Were Young, Maggie” “The Near Future (How Dry I Am)” “At the Cross” “Jenny Lind Polka” and “When You Wore a Tulip” – revived and played in a high-energy modern style, the selection provides a meta-commentary on the Anthology itself, which is similarly made up of old recordings, sometimes of even older songs, made available again in the newer, long-playing album format. Furthermore, “Moonshiner’s Dance” overtly presents itself as an advertising document of the kind of live performance that a patron might have experienced live and in person at the local Victoria Café. To demonstrate its documentary nature, the piece begins with an enthusiastic barker shouting to the audience: “Hey, hey, Mr. Larson!” The appellation was intended to evoke a common local name as being representative of an “ethnic stereotype of a hick from the vast (and partly imaginary) Scandinavian farmland” that surrounded the area. (Quotations and information from Gegenhuber.)

Moreover, on the Anthology, “Moonshiner’s Dance” provides the last example of the good-time pieces that it is collected with on the first part of the two-part volume of Social Music. There, it represents a grand finale culmination of a kind of “Saturday night out on the town” bacchanal. In stark contrast, however, it is followed by the first track of the second part of the volume, which represents a collection of the completely opposite kind of religious music that one might hear at services in church on Sunday morning following the debauch. These are introduced by “Born Again,” an incredibly serious and somber choir recording led by the Reverend J. M. Gates. (Listen at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g8Xt3bkK4E8)

The Anthology’s legacy was already cemented early on by the enormous influence that it wielded over the folk music revival of the late 1950s and early 1960s, including key protagonists such as Jerry Garcia, John Fahey, Pete Stampfel, and most famously Bob Dylan. Recognition of its importance culminated in the honorary Grammy Award that Smith received in 1991. At the ceremony, echoing his sentiment that the Anthology had been specifically created to cause social changes, he proclaimed that his dreams had come true because, “I saw America changed through music.” Indeed, this interpretation is supported by the occult elements and features that Smith inserted into the set, including the way in which each of the three volumes was color-coded to match a different element along with the wealth of mystical diagrams and quotations from Aleister Crowley and others included in the accompanying cut-and-paste informational booklet, a publication that presaged the busy, photocopied layout of later punk zines by decades.

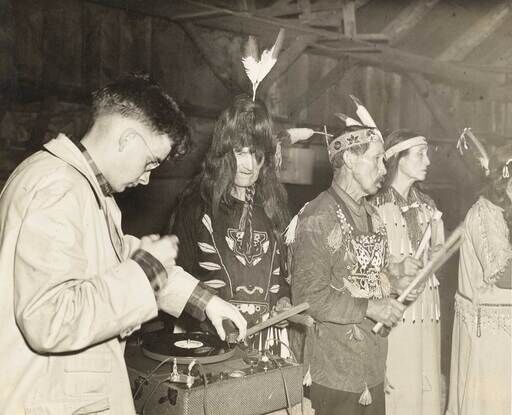

Regardless of its merits, one fair criticism that has been levelled against the Anthology is the fact that it does not include any Native American music. The omission is somewhat surprising given that Smith started his career in high school in a kind of anthropological role, collecting artifacts, recording and notating music, taking photographs, and making paintings of the culture and ceremonies of the Lummi and Salish tribes in the different areas where he grew up around Bellingham and Anacortes, Washington, in the Pacific Northwest. Later in 1964, Harry returned to these interests by traveling to Oklahoma to record songs and stories, mostly related to the peyote ceremonies, of the Kiowa. The resulting three-album set was also released by Folkways and serves as a kind of corrective correlative companion compilation that nicely complements and completes the Anthology.

In addition to these major productions, and as presaged by his high school ambition to become a composer of symphonic music, Smith created a number of other music and sound- based works throughout his productive career, most of which were also released by Folkways. After moving to New York and compiling the Anthology, Harry made extensive recordings of Prayers and Chants performed by Rabbi Naftuli Zvi Margolies. Even later, still functioning as an independent producer, Smith was responsible for recording the Fugs’ First Album in 1965, Allen Ginsberg’s First Blues: Rags, Ballads, and Harmonium Songs at the Chelsea Hotel in 1971, and the experimental multitracked album of Seven Flute Solos by Charles Compo in 1983. Smith also made extensively diverse mix tapes to give to friends to provide them with a thoroughly educational introduction to the study of world music. And finally, Harry made hours and hours of ambient cassette recordings documenting the sounds of places as varied as a Bowery flophouse filled with the coughs and other noises of dying bums in contrast with the joyous sounds of a Fourth of July Independence Day celebration at Naropa, complete with fireworks.

Even though this body of musical work alone would already ensure Smith’s legacy as an influential and interesting artist, at least in certain circles, they represent only a portion of the incredible body of work he produced with an amazing breadth, depth, and diverse complexity that encompasses a variety of different media, including painting, drawing, design, anthropological collecting, and experimental filmmaking.

“Fragments of a Faith Forgotten: The Art of Harry Smith” at the Whitney Museum of American Art

The first fully dedicated retrospective exhibition, “Fragments of a Faith Forgotten: The Art of Harry Smith,” is currently on display at the Whitney Museum of American Art from 4 October 2023 through 28 January 2024. While being limited to one room with an adjacent listening lounge, the exhibition still makes a valiant effort of demonstrating the full scope of Harry’s career by including at least some examples from all his works and collections, including a few of the rare, early “brain drawings” and other visual pieces in various media, such as two typewriter drawings. More excitingly, the exhibition also includes several items that have not been reproduced anywhere else, such as the geometric tile designs and rich India ink drawings he made for Lionel Ziprin’s companies.

However, the curators have been unavoidably hampered by the fact that much of Harry’s work was lost over the years, for a variety of reasons. The most famous example was a time in 1964 when a landlord threw all his possessions away during an eviction for lack of paying rent. In response, Harry spent several weeks going every day to the Fresh Kills Landfill in Staten Island to try to find and salvage his items, but to no avail. This episode has been identified as the moment when Smith’s mental health deteriorated badly and his subsequent drinking and other drug use became overtly and troublesomely problematic. This led to a habitually unstable state during which he was prone to destroying even more new works, film equipment, or other items such as books in fits of uncontrollable rage. As a result of this unfortunate reality, three early jazz paintings are shown only as light box projections made from slides. Other items include old mechanically reproduced records from his collection and copies of the different colored covers for the Anthology albums. Moreover, since they each depict an image of a celestial monochord, a large, functioning, and deeply resonant monochord equipped with a freely movable bridge that visitors can play is cleverly mounted on the wall next to them.

Ultimately, the exhibition makes up for these artifactual limitations by featuring a number of Smith’s lengthy time-oriented works as centerpieces, instead. They include video loops of Film #11: Mirror Animations (1957) and Film #14: Late Superimpositions (1964) displayed on small video monitors, while listening earpieces next to the jazz transcription paintings allow visitors to listen to the original recordings that inspired them. A television at the entrance to the exhibition plays Andy Warhol’s full screentest of Harry from 1964, during which he demonstrates several string figures.

Most importantly, however, the exhibition features two large screens with ambient speakers showing continuously looping screenings that visitors are able to sit and watch in their entirety of complete, newly restored copies of Harry’s two major films. The first is the complete one-hour-long Film #12: Heaven and Earth Magic (1962), a hallucinatory black-and-white animation laboriously made out of innumerable Victorian-era cutouts. The second and real centerpiece of the exhibition is the full presentation of the complete two-hour-long, four-screen opus Film #18: Mahagonny (1980). Harry described the film as “a mathematical analysis of [Marcel] Duchamp’s La Mariée mise a nue par ses celibtaires, même [The Large Glass], expressed in terms of Kurt Weill’s score for Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahagonny with contrapuntal images (not necessarily in order) derived from Brecht’s libretto for the latter work.” Furthermore, it was intended to be “just as intelligible to the Zulu, the Eskimo, or the Australian Aborigine as to people of any other cultural background or age.” (Quotations and biographical details from Szwed.)

Otherwise, sharply complementing the darkness of the main exhibition room is a reading and listening lounge housed in a large, brightly windowed room overlooking a magnificent view of the Hudson River. There, visitors can peruse two thick binders filled with photocopies of fascinating letters, such as those from the later 1940s to fellow filmmakers Kenneth Anger and Oskar Fischinger, and wonderful photographs documenting different periods of Harry’s life and career, including behind-the-scenes images of his impoverished working conditions during his stay in the 1980s at the Hotel Breslin. Facsimiles of the Anthology booklet are also included, while computer monitors display the track information as they cycle through a playlist of its tracks.

The next event scheduled at the Whitney in connection with this exhibition is “My Harry”, a three-day symposium from 8-10 December 2023 featuring friends and fans presenting talks, screenings, music, and more.

Selected Websites

Harry Smith Archives: https://harrysmitharchives.com/

Anthology of American Folk Music: https://folkways.si.edu/anthology-of-american-folk-music/african-american-music-blues-old-time/music/album/smithsonian

Cosmic Scholar: https://us.macmillan.com/books/9780374282240/cosmicscholar

“Fragments of a Faith Forgotten”: https://whitney.org/exhibitions/harry-smith

“My Harry”: https://whitney.org/events/my-harry-smith

Selected Bibliography

Harry Smith: American Magus. Paola Igliori (Editor). Semiotext(e). (2022)

Harry Smith’s Anthology of American Folk Music: America Changed Through Music. Ross Hair and Thomas Ruys Smith (Editors). Routledge. (2017). Including Kurt Gegenhuber, “Smith’s Amnesia Theater: ‘Moonshiner’s Dance’ in Minnesota.”

Harry Smith: The Avant-Garde in the American Vernacular. Andrew Perchuk and Rani Singh (Editors). Getty Research Institute. (2010)

Harry Smith: Cosmographies, The Naropa Lectures. Raymond Foye (Editor). Naropa Institute. (2023)

Harry Smith: Think of the Self Speaking: Selected Interviews. Rani Singh (Editor), Allen Ginsberg (Introduction). Cityful Pr. (1998)

John Szwed. Cosmic Scholar: The Life and Times of Harry Smith, the Filmmaker, Folklorist, and Mystic Who Transformed American Art. Farrar, Straus, and Giroux. (2023)